Here’s a fascinating report from Infoguide Penny Williams:

A pioneering art restoration project in the Puno Region of Peru has an AGO connection: Michaela Novotna, the only non-Peruvian on the team.

We knew Michaela as a P&D volunteer (2009-2014) and then as a part-time member of the Collections Management team (2014-2015). Since January 2016, she has been an external consultant to this restoration project in Ayaviri, a small city high (12,000 ft.) on the altiplano — first contributing her background in museology, now with additional roles in both art restoration and project development. She receives no salary, and her expenses are paid by a Canadian firm with interests in the area.

Michaela and I overlapped on the AGO Volunteer Executive. We’ve kept in touch, and in December 2016 I spent two weeks with her, meeting the remarkable team and seeing the remarkable work being done.

First remarkable thing: Michaela’s skills with her 1200 c.c. BMW motorcycle! Here we are (passenger-me in borrowed leathers), setting out on the 250-km trip she regularly makes between her pied-à-terre in Cusco and her project life in Ayaviri.

The project has four components, starting with and flowing from the city’s outstanding but highly stressed example of Andean Baroque architecture, the 18th-c. Catedral de San Francisco de Asís.

The project has four components, starting with and flowing from the city’s outstanding but highly stressed example of Andean Baroque architecture, the 18th-c. Catedral de San Francisco de Asís.

In 2007, newly-appointed parish priest Miguel Coquelet saw both the accumulated art treasures of this historic site, and the impact on them of centuries of neglect. With the support of his bishop, he began pushing — first for an inventory, and then for active restoration.

By the time Michaela arrived in late 2015 (friend-of-a-friend introduction), Padre Miguel had caused a massive study to be published on the history and artistic significance of the cathedral: La Catedral de Ayaviri en el tiempo. He had also won the commitment of a highly trained Peruvian art restorer and consultant to international projects, Oscar Andrés Guillén Chávez.

“That led to the next two activities,” explains Michaela, “both of them housed in a former mining company office, now owned by the Church and reborn as a Cultural Centre and Museum.”

Come through the door, and you’re in the little restoration workshop. where Oscar and a younger colleague have been steadily working on smaller objects that can be hand-carried from the Cathedral. Here she and Oscar have a quick catch-up before they take me into the Museum.

A good number of the restored 17th-c. and 18th-c. objects, ones with no role in current liturgy, are now on display in the Museum’s four rooms — one each for sculpture, paintings, silver and other liturgical objects, and regional archaeology.

I see everything from this late 17th-c. painting on linen of Señor de los Tremblores …

to an early 18th-c. portable wooden altar, taken by the priest of the day as he made his rounds to distant villages …

to an early 18th-c. portable wooden altar, taken by the priest of the day as he made his rounds to distant villages …

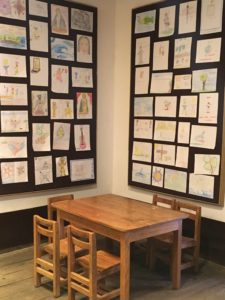

and, of course, the activity corner for visiting schoolchildren.

Final component in the Ayaviri program: a joint venture between the Municipality and the Church in basic art restoration training for 20 local students. The second of two training units was just winding up during my visit — here I catch Michaela helping one student with colour-reintegration choices. Another 4-month training unit has been funded for 2017.

Final component in the Ayaviri program: a joint venture between the Municipality and the Church in basic art restoration training for 20 local students. The second of two training units was just winding up during my visit — here I catch Michaela helping one student with colour-reintegration choices. Another 4-month training unit has been funded for 2017.

The big news: in December, after what Padre Miguel wryly calls “The Battle of 2,000 Days,” the Government of Peru confirmed it will fund a 2 1/2-year comprehensive restoration program for the Cathedral, due to start this spring after the rainy season. The priest rejoices above all for its spiritual significance, but joins Oscar and others in valuing the cultural and economic benefits as well — plus possible tourism impact, once the work is done.

“I thought I was here for just one more year,” says Michaela, “but with this program now guaranteed, the role that I and others will have within it, and the potential for using it to connect people with their heritage … oh, I’ll be here for another two and a half years, for sure.”

She waves a hand. “Or maybe twenty! There is such urgency, here in Puno Region — nothing has been done, so much is being lost, and restoration could have such cultural and economic impact.”

Next post: Side trips to an unrestored and fragile 17th-c. village church in Orurillo.

Links:

- Michaela herself, who welcomes your questions and comments: [email protected]

- Posts on my own blog about this visit, with more detail and more photos: https://icelandpenny.wordpress.com/2016/12/04/adelante-the-adventure-begins/

- Background about Ayaviri and the cathedral: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayaviri,_Melgar

- PDF of the book, La Catedral de Ayaviri en el tiempo: http://ucsp.edu.pe/fondoeditorial/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Libro-Ayaviriresumen.pdf